There has been a lot written recently about the conviction of Gilberto Valle, “Cannibal cop,” and advent of “thought crime.” (an interesting point-counterpoint at Salon, and great thorough coverage by Daniel Engber’s Slate.com) Gilberto Valle is the New York cop who fantasized in elaborate and gruesome detail about kidnapping, cooking and eating a young woman (at one time possibly his wife, at one time possibly an old college friend). He spent a great deal of time discussing this dark fantasy in that proving ground for inept criminals, the internet chat room, and on sites like darkfetish.net. He also accessed a police database to track down one of his possible victims, and actually paid a visit to one possible victim (albeit on a vacation with his wife and child). Long story made short (though if you want the longer story, really: check out the Slate coverage, linked above), his wife eventually noticed that he was spending inordinate amounts of time chatting on the computer & with some investigation, discovered his horrific plans. She turned the computer over to the FBI, grabbed their child and ran. Gilberto was arrested, tried, and convicted (& for those still following this saga, he will be sentenced June 19th – ironically, his one year wedding anniversary).

There has been a lot written recently about the conviction of Gilberto Valle, “Cannibal cop,” and advent of “thought crime.” (an interesting point-counterpoint at Salon, and great thorough coverage by Daniel Engber’s Slate.com) Gilberto Valle is the New York cop who fantasized in elaborate and gruesome detail about kidnapping, cooking and eating a young woman (at one time possibly his wife, at one time possibly an old college friend). He spent a great deal of time discussing this dark fantasy in that proving ground for inept criminals, the internet chat room, and on sites like darkfetish.net. He also accessed a police database to track down one of his possible victims, and actually paid a visit to one possible victim (albeit on a vacation with his wife and child). Long story made short (though if you want the longer story, really: check out the Slate coverage, linked above), his wife eventually noticed that he was spending inordinate amounts of time chatting on the computer & with some investigation, discovered his horrific plans. She turned the computer over to the FBI, grabbed their child and ran. Gilberto was arrested, tried, and convicted (& for those still following this saga, he will be sentenced June 19th – ironically, his one year wedding anniversary).

As I’ve been reading the coverage, I’ve been thinking a lot about the case of Daniel DePew, also convicted of a “thought crime” back in the early 1990s. Dan DePew was convicted, along with Dean Lambey, of conspiring to kidnap, abuse, and “snuff” a young boy. The catch is, this crime never occurred. The evidence that it was actually planned is thin at best – and the evidence of police entrapment was overwhelming. The history of this infamous “crime” is detailed in the early chapters of Laura Kipnis’ excellent Bound and Gagged (reviewed here): two cops, taking advantage of the “snuff film” hysteria of the late 80s, trolled internet bulletin boards until they discovered a man who claimed to have a significant stash of child porn (Lambey). They goaded him into enlisting another man – Daniel DePew – in a greater plot to create a “snuff film,” thus creating a conspiracy. Lambey found Dan DePew on – you guessed it – the internet, trolling gay S&M Bulletin Boards, putting feelers out for people with “common interests.”

The details of the entrapment are truly astonishing. Most of the ideas seem to come from the police. At first the four spin elaborate – albeit extremely dark – fantasy about kidnapping and assaulting a young boy. This fits into Dan DePew’s own S&M Practice – he admitted to being “into” Daddy-Boy scenes. But the idea of making this fantasy into reality, and the conviction that they would have to “snuff” the victim, comes first from the police! And at one point just before he was arrested, Dan DePew says that he wants out, that the whole thing had gone too far. He actually has to be talked back into the plan by one of the cops, because (as the cops well know) if there aren’t at least two non-cops involved, they cannot be guilty of conspiracy. Dan DePew was convicted & sentenced to 33 years.

So both of these men were convicted of thought crime – guilty of fantasy. Well, actually, both of these men were convicted of conspiracy to commit heinous crimes. The difference between a “pure” thought crime and a conspiracy is an “overt act” in furtherance of the alleged conspiracy. Dan DePew investigated the manufacture of chloroform – that was his overt act (the case against him grows even flimsier upon investigation). Gilberto Valle committed a number of slightly more… “overt” acts – he accessed a restricted police database to gather information on a possible victim, and actually travelled several states away to see her. The reasoning is that once there is an overt act, arresting the participants is no longer punishing an obscene fantasy – it’s preventing a murder. But was the act a clear enough indication that this was a plan, rather than pornographic imagination? That’s the question that the jury has to answer – and in both cases, they saw a plan.

But as I’m looking at these two cases, I wonder what else the jury saw. Dan DePew is a gentle giant: tall, well built, soft-spoken. But he is also an openly gay man – a cause for fear in Virginia of the late 80s, where sodomy was still a crime. He was into violent S&M when the image of the gay scene still resembled Al Pachino in Cruising. Worse still, into daddy/boy scenes. And if all of this were not enough to stack the jury against him, it was revealed in court that he had AIDS. He was the very embodiment of the demonic “other” – the jury’s greatest fear made flesh. The facts are a garish parody of police entrapment as performed by the keystone cops – and yet faced with the embodiment of evil, the jury convicted .

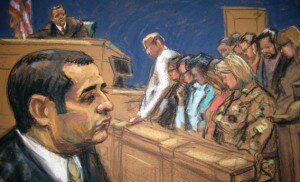

Compare that with Gilberto Valle. Officer Valle was recently married, had a new baby, grinned boyishly from dozens of photographs (again, check out the Slate coverage – great journalism). He had the look of a friendly beat-cop, someone who you could trust to teach your son or daughter about bike safety in the neighborhood. But reading the contents of his online chats about cooking and eating young women, discovering that his family vacation to Maryland was really a stalking mission, he quickly morphs into our greatest fear: the devil among us. Watching the coverage of the marathon bombings, the recent kidnapping drama in Cleveland, it seems clear that in addition to the crime itself, what horrifies us is that people guilty of such heinous acts are with us day in, day out. We see them on the street, we say hi to them … we have ribs with them. The jury convicted him for what the prosecution said he planned to do – realize his darkest fantasy by cooking and eating another person. It is very likely the jury also convicted him for who he is: our newly married next-door neighbor with a new baby and a very dark secret.

The question that runs through the coverage of both of these events is: were these men convicted of fantasy? Do we read here the advent of the “thought police” as foretold by George Orwell? Or had fantasy crossed the line into conspiracy? Did the “overt actions” taken by these men demonstrate “beyond a reasonable doubt” that they had taken steps towards committing these grisly crimes – crossing the line from fantasy to reality? I find another question here as well: did these juries vote to convict deep-seeded cultural fears: in 1990, the sado-masochistic gay “other;” in 2012, evil among us – the devil we saw every day but didn’t recognize.